I’ve been trying to go through this list more or less in order, but Kubrick’s “Barry Lyndon” represents my first big break with with that. It’s for a good reason, though: Yale’s “Treasures From the Yale Film Archive” series was screening a pristine 35mm print. How could I say no?

This was my second time seeing “Barry Lyndon,” and actually the first time was also a screening at Yale in 2019. I’m incredibly lucky to have had the opportunity twice. Obviously, the film’s reputation as a masterpiece of visual film making is well deserved. It sounds hyperbolic to say almost every frame could be a oil painting, but I really think it’s true. Seeing it on the big screen is a treat. But more than that, “Barry Lyndon” is funny — Kubrick’s script, adapted from a novel by Thackeray, does a great job of translating the latter’s authorial wit to the screen by way of an omniscient narrator — and watching it with an audience really enhances the experience.

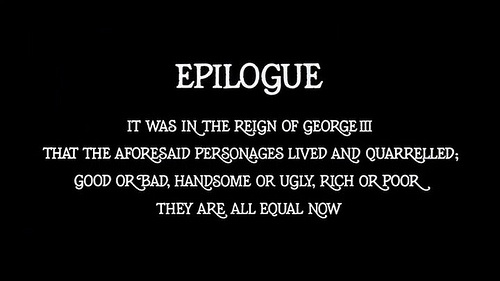

Reflecting on “Barry Lyndon” now I’m struck by a central irony. The narrator repeated refers to the events of Barry’s life in terms of fate and its will, as though he were putty in the hands of destiny. But Barry is consistently taking his fate into his own hands: He actively and deliberately antagonizes John Quinn and challenges him to a duel, prompting his departure from home. Fate may have forced his hand with regards to enlisting in the English army, but Barry himself decided to desert, which led him to his stint with the Prussians. He decided to play double agent with the Chevalier, and to pursue the Lady Lyndon, and to squander her fortune seeking his own title, and to attack Lord Bullingdon. His fate is his own. So why is the narrator so insistent on pushing all the blame onto destiny’s impersonal machinations?

Maybe he’s simply a Barry apologist, reflecting the original novel’s unreliable first-person narration. Maybe it plays into the film’s satire of 18th-century society — illustrating the absurdity of the idea that social roles and class are somehow preordained or the will of God. (That is, everyone is where they are because they or someone before acted to put them there.)

Anyway: